Note: The author would like to thank Frances Coppola for reviewing earlier drafts of this article and and providing excellent insight on modern monetary theory (of course any mistakes are mine). It is with her assistance that I have realized that both Keynesianism and Monetarism are, in way, obselete. What follows is an argument of purely theoretical value intended to show that other than purely ideological obstacles, Keynesianism and Monetarism are suggesting the same thingand any further discussion is redundant.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, other than being the two most influential economists of the 20th century were the originators of two schools of thought which have sustained a debate for a full 50 years (Friedman published his "A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960" book in 1963). Although both schools of thought are in agreement that the aggregate demand curve (i.e. output) is downward-slopping they are in disagreement about what causes the curve to shift.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman, other than being the two most influential economists of the 20th century were the originators of two schools of thought which have sustained a debate for a full 50 years (Friedman published his "A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960" book in 1963). Although both schools of thought are in agreement that the aggregate demand curve (i.e. output) is downward-slopping they are in disagreement about what causes the curve to shift.

Monetary Theory

Monetarists use the quantity theory of money in their view of aggregate demand:

M*V=P*Y (1)

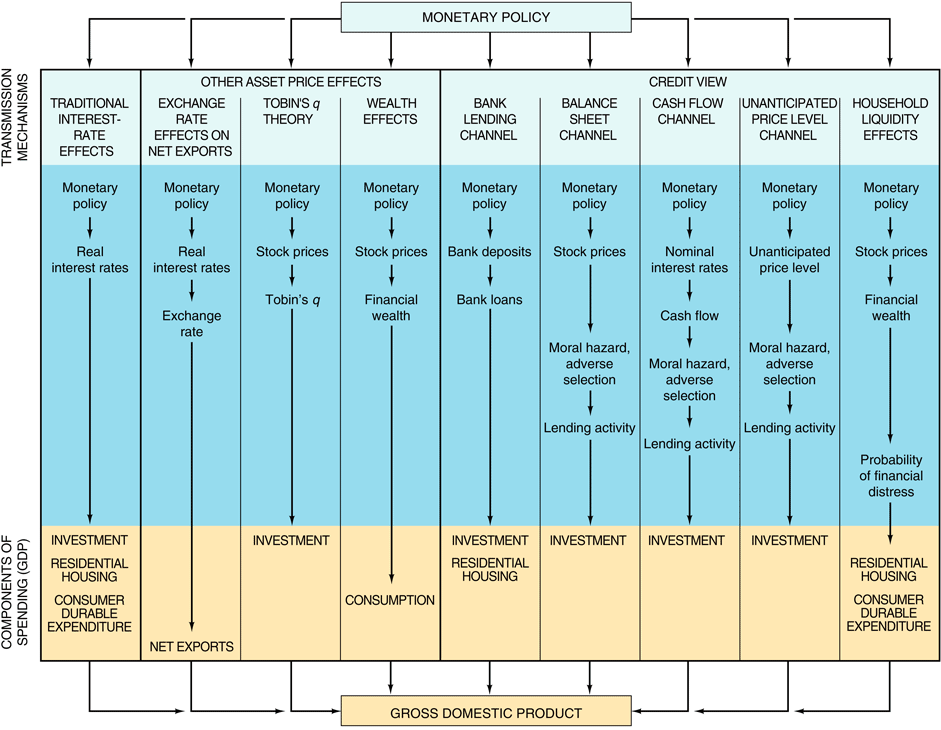

with M being the quantity of money in the economy, V the velocity of money (i.e. the average number of times per year that a unit of currency is spent on final goods and services), P is the price level and Y is aggregate real output (or equivalently, real income). Using the above identity, monetarists argue that in order for output to increase, a rise in the money supply has to occur. (for example, if V=1 and P=2 are constant, then in order for Y to increase M has to increase). The monetary policy transmission mechanisms are summed up in the following table (Click to Enlarge):

|

| Source: Frederic Mishkin, Economics of Money, Banking, and Financial Markets, 9th edition |

Keynesian Theory

In the Keynesian framework

Y=C+I+G+NX, (2)

with Y being output, C consumer expenditure, I is planned investment expenditure, G government spending and NX being net exports (i.e. Exports-Imports). In the Keynesian view, if the price level (P) falls, while M is constant, the quantity of money in real terms is larger, thus causing the interest rate to fall which in turn makes investment grow. Thus, output (Y) grows as well. A similar argument is made by saying that after the interest rate falls, currency depreciates, net exports increase thus output increases again.

The main difference between the two theories is that Keynesians believe that factors other than the money supply are also important in causing the aggregate demand curve to shift. More importantly, it is the change in Y which causes the change in M. Increasing the current state of output depends on factors include manipulation of government spending and taxes, changes in net export and changes in consumer and business spending.

Two sides of the same coin

The Keynesian premise states that increased government spending or a reduction in taxes makes people have more to spend than before; either because they give away less in taxes or because increased spending increases their income. Here, the debate of crowding out private spending occurs (i.e. if the increase in government spending will induce a decrease in other parts of the output equation, notably private investment and spending, thus leaving it unaffected). Nevertheless, crowding out only occurs when the economy is in full capacity and not at any other level (the only other possibility is when the state effectively steps in to take private sector jobs, yet this is irrelevant of whether the approach is one or the other). However, what most monetarists do not observe is that the case of government spending not being done by issuance of government bonds (i.e. borrowing) but by printing new money, is practically the same as increasing money supply in the first case of the above picture (although in the modern economic system either borrowing or printing would be more or less the same). Thus, if increased government spending is done via the printing machine then the monetarists' argument of crowding out the private sector cannot hold as it would necessarily have to hold when we use the monetarist doctrine (in which case crowding-out does not happen as theory and practice state). This means that both the Keynesian and the Monetary doctrine are in fact promoting the same issue, albeit with different ideology.

Either increasing government spending or increasing the amount of M in the economy would have the same result. Printing money would equal increasing government spending (e.g. build more roads) since you actually have to use that money somehow and not just have them lying around; and you cannot throw it over the country with a helicopter (well you can, but it's not a very good policy!). Thus, unless we speak of creating money and giving them to the banks so they can increase lending (which again is not good policy as it is subject to the whims of the banking system), printing is the same as increasing government spending (one may argue that the money can be used to finance the same amount of spending as before, yet this will also affect the economy albeit indirectly through decreased supply of government bonds).

It appears that Monetarists cannot accept that changes in consumer and business spending also affect output. This is somewhat against their own logic once again: Note that in identity (1) the quantity theory of money states that "keeping all else constant" only M can change Y. Yet, an increase in consumption (keeping M constant) means that the average times a euro is spent over a year (i.e. V) increases. If V increases then (keeping everything else constant) it means that either P or Y have to increase. Nevertheless, if P (the price level) is affected only by the money supply in economy (according to the monetarist theory), then it cannot be increased without an increase in M. Thus the only part of the equation which can be increased is Y.

The point here is that inflationary pressures will occur whatever the approach may be. Yet, this is exactly what policy should be aimed at: as real interest rates increase and nominal rates decrease during a recession (just have a look at Japan currently or at the US during the Great Recession) the only way to induce spending is by increasing these rates. Both theories provide some good tools for this although they present it differently:

1. Monetarists say that an increase in the money supply will increase output.

2. Keynesians say that an increase in government spending or a reduction in taxes will do that.

Nevertheless, when we replace "government spending" with "government spending via increasing money supply" instead of borrowing then the Keynesian doctrine is identical to the Monetarist one. Krugman and DeLong point out that in a liquidity trap government lending will not cause interest rates to rise. In addition, Krugman comments that the IS-LM (Keynesian) model equals the Modern Monetary Theory one once a country finds itself in a liquidity trap. The argument here is that the two approaches are the same not just in a liquidity trap setting but in recessions in general (in a liquidity trap it would be actually easier to go through with fiscal stimulus since it does not require the same amount of commitment as a monetary expansion). Then, since crowding out effects do not occur during a money supply increase if we trust the Monetarist view on the subject, we are forced to conclude that they do not also rise even if the channel is increased government spending.

In practice, both theories should work well in a recession as long as the government steps in to cover for the private sector's unwillingness to invest or consume; both are also expected to be inflationary and cause private sector crowding out at times where the economy is operating at full capacity (or if supply-side inefficiencies occur). Thus, what is left when all economic arguments lifted is pure ideology: is a large government sector better than a small one? And the answer, similar to all issues of economics and life is, it depends...

In practice, both theories should work well in a recession as long as the government steps in to cover for the private sector's unwillingness to invest or consume; both are also expected to be inflationary and cause private sector crowding out at times where the economy is operating at full capacity (or if supply-side inefficiencies occur). Thus, what is left when all economic arguments lifted is pure ideology: is a large government sector better than a small one? And the answer, similar to all issues of economics and life is, it depends...